denkyemase

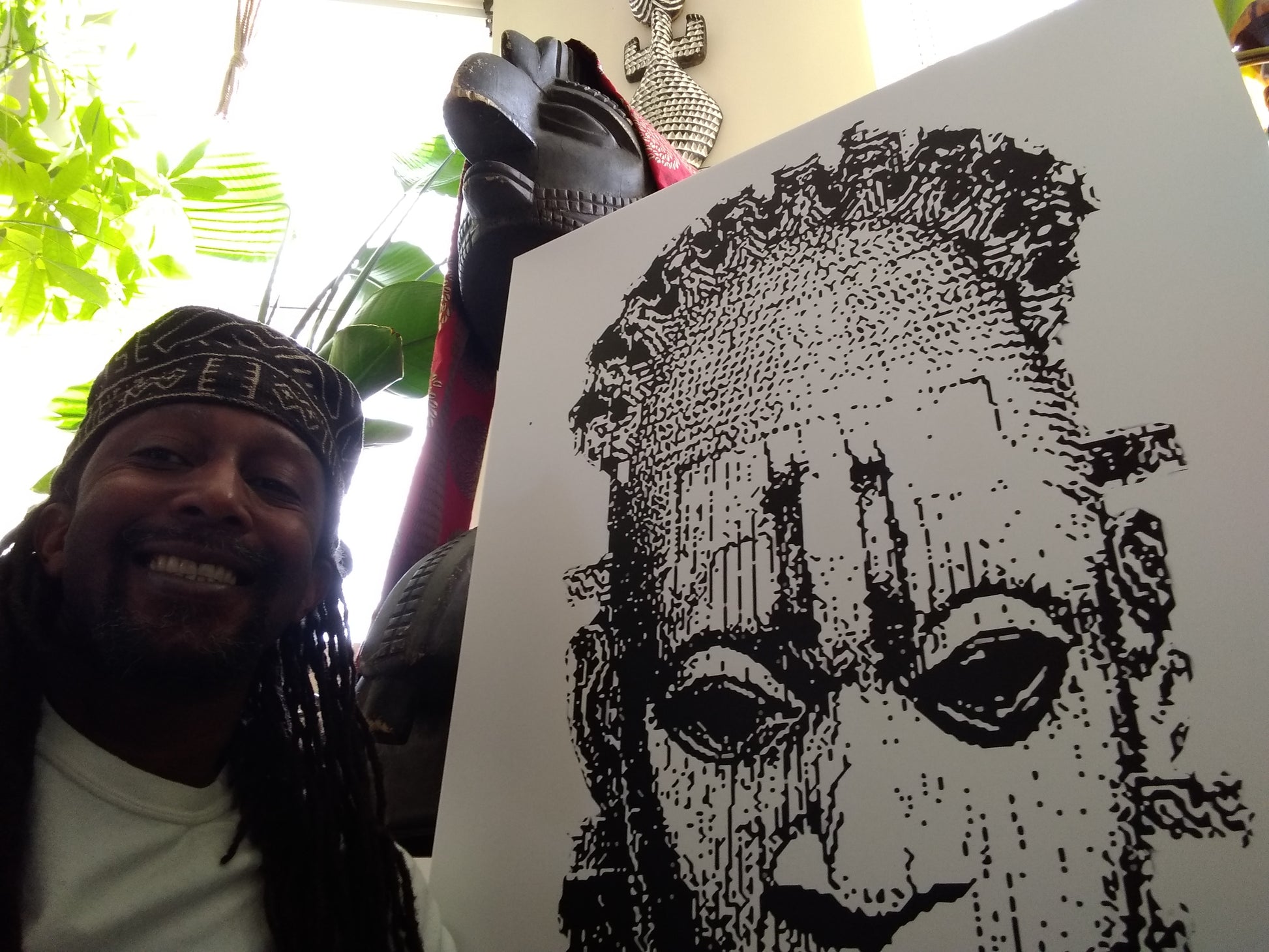

DENKYEM ASE "Benin Bronzes Queen Mother Idia Mask" 24"x48" X-Large Foam Board Print

Couldn't load pickup availability

24"x48" X-Large Foam Board Print - Queen Mother Idia Mask

- Durable, 5 mm foam

- Smooth matte finish

- Vivid, full-color UV printing

“Generations of Africans have already lost incalculable history and cultural reference points because of the absence of some of the best artworks created on the continent. We shouldn’t have to ask, over and over, to get back what is ours.” ----Victor Ehikhamenor, New York Times op-ed 2020

This Benin ivory mask is popularly known as the Queen Mother Idia Mask. It is a miniature sculptural portrait in ivory of Idia, the first Iyoba (Queen Mother) of the 16th century Benin Empire, taking the form of a traditional African mask. It was usually worn by Benin Kings on royal ancestral ceremonial occasions and was last worn by King Ovoramwen who was dethroned at the fall of the Benin Empire in 1897. The same year, it fell into the custody of Sir Ralph Moor, the Consul-General of the Niger Coast Protectorate as it was looted alongside other aesthetically crafted Benin Arts from the palace of the Oba of Benin in the Benin Expedition of 1897.

The Benin Bronzes are a group of thousands of objects that were taken from the kingdom of Benin, in what is now Nigeria, in 1897. (Their exact number is unknown, though it is believed to exceed 3,000.) These objects—including figurines, tusks, sculptures of Benin’s rulers, and an ivory mask—were looted by British troops, and have since been dispersed around the world, with the bulk of the works now residing with state museums in Europe. Contrary to the name, not all of the works are made of bronze. Because they made their way beyond West Africa as a result of a colonial conquest, the Benin Bronzes have faced calls for their return, both within Nigeria and outside it.

In 1897, James Phillips, an unarmed British explorer, visited the Kingdom of Benin. The kingdom’s ruler, the Oba Ovonramwen, welcomed Phillips, who decided to continue the expedition, even though he had been warned not to come to the Oba’s kingdom during a sacred period for its members. Chiefs reporting to Ovonramwen believed that Phillips and his expedition would interrupt a series of rituals, and a dispute occurred. Phillips, several in his mission, and 200 African porters were killed. To avenge their deaths, the British empire sent troops to steal artifacts from the kingdom, and they walked away with thousands of priceless objects. Some were placed on loan to the British Museum by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in England, and many more were sold to British and German institutions, as well as private dealers. According to the British Museum’s website, certain people who took part in the Benin expedition also kept Benin Bronzes for themselves.

In 1977, FESTAC ’77, a Lagos arts event that took as its title the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, used a 16th-century ivory mask once worn by an Oba as its symbol. FESTAC is the acronym for the second edition of the World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture which was held in Nigeria between 15th January and 12th February 1977, in Lagos and Kaduna during the administration of the then Head of State, Lt. Gen. Olusegun Obasanjo.The First edition took place in Dakar, Senegal from 1st -24th April 1966. For FESTAC ’77, a replica was made by a Benin Sculptor, Erhabor Eneokpae after several attempts by the Nigeria Government to have the original retrieved from the British Museum where it is till this date.

There are four known copies of the mask, with the most well-known one residing at the British Museum in London, where it is on permanent display. In the run-up to the festival, Nigerians began clamoring for the return of the British Museum mask, and when that became impossible, a committee began seeking a loan. That, too, never came to pass.

Nigerians have continued to demand that museums across the world give back their Benin Bronzes. The Lagos- and U.S.-based artist Victor Ehikhamenor, for example, wrote an impassioned New York Times op-ed on the subject in 2020. His essay concluded: “Generations of Africans have already lost incalculable history and cultural reference points because of the absence of some of the best artworks created on the continent. We shouldn’t have to ask, over and over, to get back what is ours.”

Institutions on several continents hold objects from the Benin Bronzes group, many of which are considered highly valuable. The British Museum has the most Benin Bronzes of any institution worldwide, with 900 objects from the group in its holdings. Because of the vast number of Benin Bronzes in its collection, the British Museum has repeatedly been the subject of protests from activists, scholars, and artists who claim that the institution owns stolen property. Berlin’s Ethnological Museum—now a part of the newly built Humboldt Forum, which also houses a research laboratory—has also faced pushback because it owns more than 500 objects from the Benin Bronzes cache, as well as other works that various figures have claimed should be repatriated to their former owners.

Yet these are but two of the many museums around the globe that hold Benin Bronzes. In his 2020 book The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution, scholar Dan Hicks compiled a list of the 161 institutions that have acquired Benin Bronzes by various means. His list includes the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac in Paris, the Vatican Museums, the Australian Museum in Sydney, the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, and the Louvre Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates. Whereas 45 U.K. institutions and 38 U.S. institutions hold Benin Bronzes, just 9 Nigerian ones own objects from the group, according to Hicks’s count.